Rural and Remote Content

Select a task below to get more information:

Task 1: Convening a stakeholder coalition & setting up a planning group

Task 2: Mobilizing readiness through social marketing framing your message

Task 3: Developing a program model

Task 4: Choosing host agencies

Task 5: Securing funding

Task 6: Hiring staff

Task 7: Developing housing protocols

Task 8: Involving people with lived experience

Task 9: Connecting with landlords

Task 10: Developing an evaluation plan

TASK 1: CONVENING A STAKEHOLDER COALITION & SETTING UP A PLANNING GROUP

In addition to working with the stakeholders already being recommended in the toolkit, rurally there may be a need to include a few others.

- Regional and systemic authorities/leaders which also may be in the closest urban centres but must be included as they are often the recipients of the homeless migrating out of the rural areas due to not being able to access necessary resources in their home community. In this context, rural homelessness impacts the urban centres based on:

- Additional cost to address individual needs,

- Reduced housing and support space for the homeless already in the urban community due to influx of people migrating.

- The need to better provide supports within the rural communities which will allow individuals to remain in their community if they so choose.

- Outreach or home care nurses who may be connecting with people in rural settings.

- Rural mental health offices.

- Indigenous leadership are especially important. If there are Indigenous people within the homeless population, rurally, there is much more need to work collaboratively across each region with the surrounding First Nations, Metis communities, and Inuit Nunangat. This is particularly important in the northern regions.

- with the local Bands as they are generally located rurally as well.

- Rural law enforcement which would include RCMP, Tribal Police, Territorial police, First Nations Police, or other rural law enforcement bodies.

- Schools

- Potential rural funders such as County or Municipal District offices and local service clubs. Do not forget to consider potential Community Entities within urban centres as they may have jurisdiction over rural areas also for funding purposes, particularly through Reaching Home dollars.

- Income assistance organizations will usually have rural communities within their boundaries.

- Even though they are often not considered, it is important to include local rural businesses such as farm implement dealerships, grocery stores, gas stations, convenience stores, hardware stores, banks, etc. Although not directly associated with homelessness, they may value their community and see the impact this problem is having and see the benefits of being involved, even if it is just by way of financial donations or support.

- Most rural communities have church affiliations which are often a great source of support with a willingness to get involved.

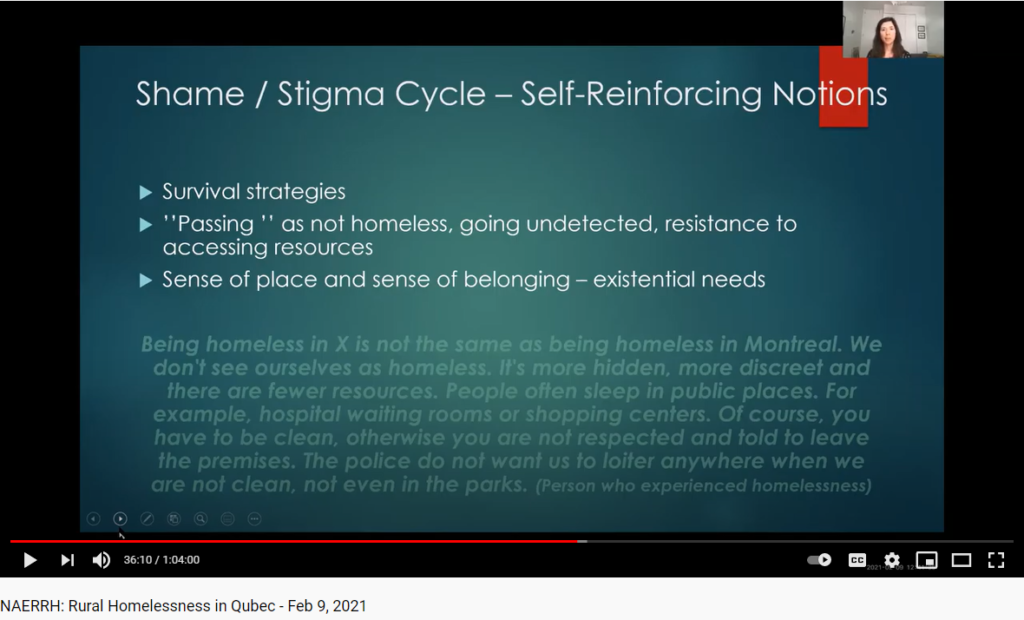

- People with lived experience are just as important to include in rural efforts to help the homeless and will have important insights related to the rural homelessness picture. This can be challenging for some as the stigma of being seen as homeless often results in public criticism and exclusion from full integration within the community. In-turn, this can result in people feeling compelled to leave their community which could exacerbate their homeless situation. Therefore, effort must be made to educate the public and ensure that stigma does not become a barrier to involving those with lived experience.

- Community members at large need to be aware and offered the opportunity to participate.

- Rural hotel/motel owners and any existing landlords and developers that may reside or work in that rural area as they may be helpful resources for accessing and creating alternative housing options.

- Local housing corporations if they exist in the rural area are important to connect with in any homelessness response movement.

Developing awareness about the extent of a homelessness problem, which produces interest among potential stakeholders, is essential but comes with different challenges in rural settings. Enumerating the homeless is challenging anywhere but performing this task in a rural environment becomes even more challenging as you often do not blatantly see the homeless but we are dealing with hidden homelessness more predominantly. Kauppi, (2017) reported that hidden homelessness is estimated to represent 80 per cent of those rurally that have no place to call home. In an urban setting, we often equate homelessness, particularly chronic homelessness with those that we see sleeping on the street, in parks, abandoned cars, and other “rough” locations. Rurally, sleeping “rough” may look different. There are people living in garages, vehicles, tents, barns, and couch surfing with many not making their situation obvious. European reference people living in boats, removal vans, and tents. It is accepted that homelessness is more hidden in smaller communities, and those in need rely on informal networks to couch surf/double up. It is difficult to account for those who sleep rough or in unsafe dwellings, seasonal “cottages,” and recreational trailers during all seasons. Many experiencing homelessness rurally choose to put up with less than appropriate accommodations because they do not want to come forward with their position for fear of stigmatization and many of the housing options that might be available would take them too far away from family and friends. Maintaining sensitivity to these factors is important yet it is also essential that rural communities and regional authorities need to be aware of these predicaments to organize and support change to better assist those experiencing homelessness.

Due to the unique circumstances surrounding rural homelessness, it is important to have rural and remote friendly methods of enumerating. Without a comprehensive needs assessment to determine the magnitude of the issue locally, and the needs of the population, service providers and advocates were hampered significantly. Therefore, specific rural and remote considerations are important; including the following:

- Types of effective rural homeless counts

- Registry weeks which help to provide more robust information to assess actual need of individuals experiencing homelessness. Some European agencies refer to this as “rural housing needs tests.”

- Period Prevalence Counts (PPC), which are similar to a registry week and are more effective for rural communities as they are completed over a period of seven to 10 days and involve engaging the entire community to locate individuals who are experiencing homelessness.

- Point in Time counts likely ineffective rurally due to them being primarily based on the visible homeless at specific times in a day during a specific day of the year. Rural homelessness is primarily hidden homeless.

- Focused approach to prioritize specific sub populations.

- Indigenous people on- and off-reserve require targeted approaches to overcoming complex jurisdictional barriers to services and supports (Christensen, 2011; Peters & Craig, 2014).

- Victims of domestic violence in many rural communities need alignment with housing and homelessness responses as there is a higher prevalence in rural locations but with less options for services and supports in place.

- Targeted responses to youth, seniors, and newcomers’ housing stress and homelessness in rural communities also need to be developed.

- while some dynamics are similar in both urban and rural homelessness (mental health, addictions, domestic violence), they may not have the same prominent role in all communities, which suggests the need for an in-depth scan and/or service mapping process is essential.

- The Indigenous perspective must be considered. “While Aboriginal homelessness is a significant urban and reserve problem, it is important to recognize this as a significant issue requiring its own attention” (Belanger & Weasel Head, 2013). This suggests that in addition to thinking from a rural and remote context, considering things like the lack of resources and supports, there is also the need to work separately with Indigenous leaders to determine how Indigenous specific factors must be considered regardless of the location of the problem.

TASK 2: MOBILIZING READINESS THROUGH SOCIAL MARKETING FRAMING YOUR MESSAGE

When it comes to readiness for change in the rural and remote context, social marketing is equally as important. Housing First will not be as well understood and may not even be recognized by many rural citizens. Awareness and understanding of what it is and how it will be of benefit will often require starting from the basics to explain the model and what it means. This toolkit already fully describes what should be the focus of these key messages. The toolkit discusses potential modifications to the core model. However, recent learnings, particularly from Housing First proponents in Europe, suggest that modifications are not needed as much as an understanding of the model’s acceptance of a spectrum continuum of model adherence or fidelity.

In addition to the concepts already addressed in the toolkit, the rural and remote model needs to be open to expansion or allowances for this continuum concept. The focus of your services can be on anyone experiencing homelessness keeping in mind the value of prioritizing people into services and supports initially based on those in your community that require the most support. Choice in housing is always going to be based on the available housing stock. Even if there are no housing options at the time, consumers can still have the choice to continue to receive supports as housing options are explored and sought out. That is still choice. Because there is often a lack of housing options, particularly scattered-site market rentals, “housing” must be expanded to allow more creative forms of permanent and stable options and be accepted as part of the Housing First approach. But the key is individuals being able to choose from existing options or choosing not to accept something offered to them without fear of repercussions or losing their level of priority.

TASK 3: DEVELOPING A PROGRAM MODEL

Creating a program model in a rural and remote environment, just like in any environment, means initially being clear about what Housing First is and how much of the model, philosophy, or even intervention need to be adapted. Or communities may simply need to acknowledge that there are areas that will be less complete than others based on the rural context and therefore need to be measured on a continuum. Some key elements of developing and implementing Housing First that have been shown to be confusing for those in rural areas include:

- Housing being a basic human right. All people should be given access to appropriate and affordable housing options without preconditions of participation in supports or treatment imposed on them.

- People should have access to supports and services without preconditions of treatment or sobriety or even housing. This means that we should not expect people to make changes in their current behaviors or seek out and commit to various treatments before they will be offered housing opportunities.

- Consumers should have choice in housing with access to subsidies where necessary. This highlights the importance of giving individuals as much choice as possible in the type and location of housing as well as choice to not accept housing if not desired without repercussions. It also suggests that subsidies should be available on a priority basis to those that cannot afford existing housing costs.

- Programs should have access to individualized, Recovery Oriented, and a participant-driven array of supports and services. This component speaks to the value of having many support options that people can access according to their needs and wants and that will address their unique situations. A harm reduction approach should be incorporated as well as efforts to support individuals with community and social integration.

- Program structure should consist of case management support and other key features. Case management may be best approached using clinical teams but as mentioned, this may not always be possible in both rural and urban settings. However, case managers should have the necessary training for this type of work and there should be an appropriate number of case managers to handle the expected number of participants. Regular team meetings should be occurring to effectively monitor and manage the day-to-day activities of the program.

It is important to understand the difference between philosophical principles, program interventions, and systems intervention when it come to Housing First. There is a difference between whether a program is a Housing First model or if they are “Housing First Friendly” which means that they support the philosophy but may be unable, due to mandates, policies, or other factors to actually completely practice based on the Housing First model. This also suggests the importance of understanding the difference between an organization or agency that is fully committed to Housing First and is only hindered by available resources and means, versus one that is being held back by policy or unwillingness to adjust mandates even if necessary resources were available to meet all fidelity elements completely. Essentially, a program should not be penalized as not being “Housing First” based on the inability to be perfect in its deliver when the shortfalls are based on challenges that are out of their control.

For additional information refer to the primary tasks identified in this toolkit.

TASK 4: CHOOSING HOST AGENCIES

Choosing a host agency really implies determining who will be responsible for the delivery of the Housing First approach. Obviously, due to other complications and limitations associated with rural and remote service delivery, this may be a challenge.

- There may not be an actual support organization equipped with appropriate staffing located within the rural boundaries.

- If there is such an agency, there is likely a lack of capacity, either with the number of staff or appropriately trained staff such that this task can be undertaken successfully.

- Distance and travel restrictions such as a lack of funding for mileage costs may make it difficult to regularly connect with persons needing supports. The distance between individuals on a case load may make it difficult to effectively serve a full case load which means adaptation of case load ratios must be considered.

Adjustments to the typical Housing First model when it comes to a host agency, will need to be considered. Creativity and adaptability to circumstances and environment are important. It may be necessary to take more of a regional approach using a collaborative model where multiple agencies pool resources to create a team that will handle a specific rural caseload rurally. Therefore, more than one host agency may be necessary. This may allow for a more flexible use of funds as well with some agencies possibly having more available funding than another, but with an appetite for focusing solely on providing the best service possible, dollars are lumped together for the greater good. Funding may also allow for the creation of a new agency in the area strictly for the purpose of being the host agency.

TASK 5: SECURING FUNDING

For rural and remote communities, there is often a key barrier when it comes to funding not faced by urban centres. The higher order of governments’ resource allocation patterns generally follows population-based formulas to determine small community shares of social support dollars, resulting in urban centres taking most of the available funds. This, exacerbated by the lack of fiscal and human resources to apply for the scarce funding available to rural communities, and the discouragement that comes with having funding applications denied can create bleak funding circumstances rurally. This does not mean all is lost.

More and more federally funded Community Entities (CE) are seeing the impact and existence of rural and remote homelessness. They are also seeing more clearly, the migratory process of people experiencing homelessness occur which puts added pressure on the homeless serving system in urban centres. This means there is more interest in putting resources into funding rural programs and plans for addressing the problem rurally. Rural communities should reach out to CEs to explore these options. They may not immediately can provide said funding, but it is important to explore and continue to advocate for this.

Federal funders such as Employment and Social Development of Canada (ESDC) who developed and manage the Reaching Home program are also becoming more aware and having greater urgency in helping rural and remote communities have access to necessary supports. Communication should continue and be enhanced with these bodies to further discuss possibilities.

Lastly, there are local organizations that will have a vested interest including all the stakeholders mentioned earlier. As these groups are pulled together to learn and discuss, desire often develops to do more, and funding must be a key topic. Even local businesses may take an interest in assisting.

TASK 6: HIRING STAFF

In rural and remote areas, staffing a Housing First program poses challenges that are not always a factor in more urban centres. Many rural programs are run and/or staffed by volunteers due to a lack of available funding. It is essential that staff are paid for this work and paid well. Trained individuals are less open to moving to more rural communities. The communities themselves have less people to draw from, and if people to come to rural areas, it is difficulty to keep them longer term as rural programs serve as good training ground to prepare someone for bigger, higher paying jobs in other locations. Typically, staff are paid less in rural communities which contributes to this high turnover.

These challenges, however, do not mitigate the need for quality staff to do this challenging work. If creating or building a team with clinical staff such as an ACT team is possible, then that should be a priority. This lessons the need for referring people to supports that may not exist if you can have individuals with clinical skills to address addictions, mental health, or other specific needs. But if not it is important to know that creativity is allowed in structuring and staffing a Housing First program.

Again, it may be difficult to draw an entire team from one organization. Likewise, there may not be funding to create a new program. This is where the idea of collaborative teams come into play and are a feasible option. Other places will use staffing from various locations but are managed or monitored by a common team lead to ensure consistency in service provision and adherence to the Housing First principles.

TASK 7: DEVELOPING HOUSING PROTOCOLS

Although Housing First is not housing only, and technically not a housing program, but instead more about recovery and helping people to have what they need to improve their lives, housing remains an integral element. We have already established that in rural areas, housing options can be very limited. For that reason, it is important to explore creative and new options. Rural housing tends to be largely single unit, free-standing housing, with some small multi-unit dwellings available in slightly larger locales. There are thus fewer living units available and few developers willing to undertake building low cost or affordable housing. The demands of rural housing include tending to heat and utilities, and sometimes the lack of adequate services. Things like snow removal becomes an additional burden while other living demands include reliable transportation in order to access food and health services, since public transportation is generally non-existent

Often people experiencing homelessness will try to move to or register for housing in larger urban centres because they feel they have a better chance at receiving housing. But what they do not realize is that the wait lists are generally longer and there are much higher numbers of people experiencing homelessness in cities. It is important that rural communities attempt to encourage and keep people locally. Even though there may be what appears to be less housing, there is still likely a greater chance of accessing something because the wait lists are much shorter.

Some examples of options for increasing or defining acceptable housing stock in rural communities include:

- Complete a comprehensive housing and service infrastructure plan to address housing instability in smaller centers as part of broader regional responses Kauppi, Pallard, Lemieux, and Matukala Nkosi, 2012; Schiff & Brunger, 2015)

- Capital projects available through federal funding initiatives such as the National Housing Strategy.

- Tiny houses

- Rooming situations (Fort McMurray)

- Boarding houses

- Smaller multi family semi-detached units or complexes (Ireland pictures of social housing examples, Scotland pictures, Canada examples)

- Secondary units

- Coach houses

- Laneway houses

TASK 8: INVOLVING PEOPLE WITH LIVED EXPERIENCE

Even in the rural and remote environment, peer support or peer specialists are essential for achieving the greatest outcomes. But due to common challenges already discussed that exist in the rural context, there is more of a need to be creative and flexible in how Lived Experience (LE) is incorporated. But if possible, it is of utmost importance to incorporate LE positions like regular members of a paid team.

‘Peer support means receiving support and understanding from someone who’s equal, has had similar (not necessarily the same) experiences and insight.’ Peer2Peer Group

‘Peer support came in with the first group when we met about 13 years ago, becoming supportive, exchanging phone numbers – it evolved rapidly.’ CAPITAL Group

‘Peer support is a system of giving and receiving help founded on respect, shared responsibility and mutual agreement of what is helpful.’ Mead et al 2001

‘When someone has spent an awful long time being misunderstood in the mental health system, peer support is like a breath of fresh air and can be lifesaving. I have found, during frequent stays in hospital, that the contents of my file seemed to be more important than my presenting state of mental health. 90% of the time I just want to talk to someone who can truly understand and can offer solutions they used themselves to overcome similar experiences – it is liberating. I am not a diagnosis; I am a human being and as such I am more important than my diagnosis. Peer Support sees the person first, understands their distress and can offer true solutions that the Supporting Peer has used themselves.’ Peer2Peer Group member

Peer support is about people with lived experience supporting each other in their wellbeing journey. It may be:

- Informal and usually provided on a voluntary un-paid basis

- Peer Specialist role in Housing First ACT team

- Peer Specialist role in ICM team

- Formal or as it’s also called ‘intentional’ – where the peer support worker is usually paid

- Case managers in Housing First programs

- Consultants to case managers or Housing First programs

- Outreach workers or supporting roles to outreach workers

- Intake workers in Housing First programs or systems

- Team leads to Housing First programs

- Committee members (members at large, Chairs, etc)

- Peer advisory committee members

- Peer organizers

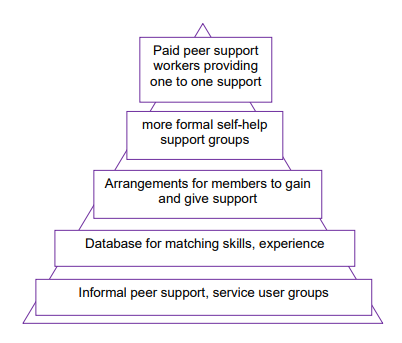

Pyramid of Peer Support (with thanks to Rochdale WRAP group)

The Lived Experience information shared in the other parts of this toolkit should be considered valuable and valid information as well.

TASK 9: CONNECTING WITH LANDLORDS

Please review the information on this topic in the main tasks.

Outside of this information, it is important to include all property owners and property managers that have interest in helping in conversations. There may be a place in rural and remote locations for programs such as shared accommodation if people have extra rooms in their homes, they are willing to rent. But it is important to keep in mind that every effort should be made, regardless of the type of housing, to work with landlords on ensuring that standard rental agreements are in place giving tenants as much opportunity to standard leasing rights as possible.

TASK 10:DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION PLAN

Please review the information on this topic in the main tasks.

For rural and remote programs please refer to this Housing First Fidelity Checklist . It is encompassing the same components as the standard Fidelity Checklist however there are some wording changes to be more rural and remote friendly and considerations are made for the rural and remote context.