Key Questions

Select one of the common questions below to get more information:

What is the goal of Housing First?

What is the problem Housing First seeks to address?

What is the cost of homelessness in Canada?

What are the origins of Housing First?

What are the core principles of Housing First?

What are the key components of Housing First?

What is Housing First – A Philosophy, a system approach, or a program model?

How is Housing First different from supportive housing approaches?

Why does Housing First emphasize consumer choice?

How does Housing First promote recovery?

Where has Housing First been implemented?

What is the evidence base for Housing First in Canada?

How can the Housing First model be adapted?

How does Housing First improve the quality of life of participants?

What is Housing First?

Housing First is a consumer-driven approach that provides immediate access to permanent housing for people experiencing homelessness, without requiring psychiatric treatment or sobriety as determinants of “housing readiness”1,2,3. Additionally, the Housing First approach is guided by the idea that housing is a basic human right4. Consumer choice is central to the Housing First model and guides both housing and service delivery.

Consumer choice is central to the Housing First model and guides both housing and service delivery. Housing First is a specific program approach, but it can also be looked at as a philosophy of service, and as a systems approach for addressing homelessness.

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is an approach designed for participants with high needs, including psychotic disorders. A multidisciplinary team, including a psychiatrist and a nurse, provides services and supports. At least one peer specialist is on staff. The client/staff ratio is 10:1 or less. Services and supports are provided seven days/week with 24-hour crisis coverage, and the team typically meets daily.

Within the Housing First model, clinical and support services are separated. Housing First participants receive housing allowances that enable them to secure typical housing in the community, and an off-site clinical team provides the support. Participants contribute no more than 30 per cent of their income for rent, sometimes from disability benefits. Participants typically live independently in scattered site apartments in the community, although they can choose to live in other housing arrangements (i.e., congregate housing). Along with housing, participants are offered an array of clinical and support services, which are individualized, flexible, and community-based. Services typically entail Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) for participants with higher needs, or Intensive Case Management (ICM) for individuals with moderate needs. ACT and ICM teams both provide community-based clinical care to individuals with mental health issues. ACT services are delivered in a multidisciplinary team, whereas ICM services are coordinated or “brokered” by a case manager.

What is the goal of Housing First?

Chronic homelessness refers to individuals, often with disabling conditions (e.g. chronic physical or mental illness, substance abuse problems), who are currently homeless and have been homeless for six months or more in the past year (i.e. have spent more than 180 nights in a shelter or place not fit for human habitation). **To the extent possible, communities should prioritize those people who have been homeless the longest.

The goal of Housing First for individuals with mental health and addiction challenges who have experienced chronic homelessness is to promote recovery.

This is accomplished first by ending their homelessness and then by collaborating with them to address health, mental health, addiction, employment, social, familial, spiritual, and other needs.

TED talk from Dr. Sam Tsemberis about the goal and origins of Housing First/Pathways to Housing.

What is the problem Housing First seeks to address?

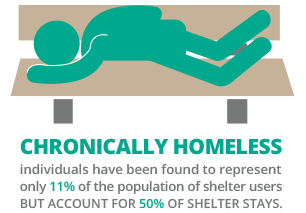

Housing First was developed to address the problem of chronic homelessness. Individuals who have experienced chronic homelessness have been found to represent only 11 per cent of the population of shelter users but account for 50 per cent of shelter stays.5,6

This group, which includes a disproportionately high number of people with serious mental illness (and often addictions), represents a subset of the homeless population who tend to stay homeless for long periods of time and who are considered “difficult to house.” People who are chronically homeless tend to cyclically use emergency health services, hospitals, and the justice system, resulting in substantial costs. Housing First addresses the social circumstances of adults who are chronically homeless and living with mental health and addiction issues by first ending homelessness and then supporting participants in their process of recovery. While the model was originally developed to address chronic homelessness, its principles can and have been applied to address other forms of homelessness.

What is the cost of homelessness in Canada?

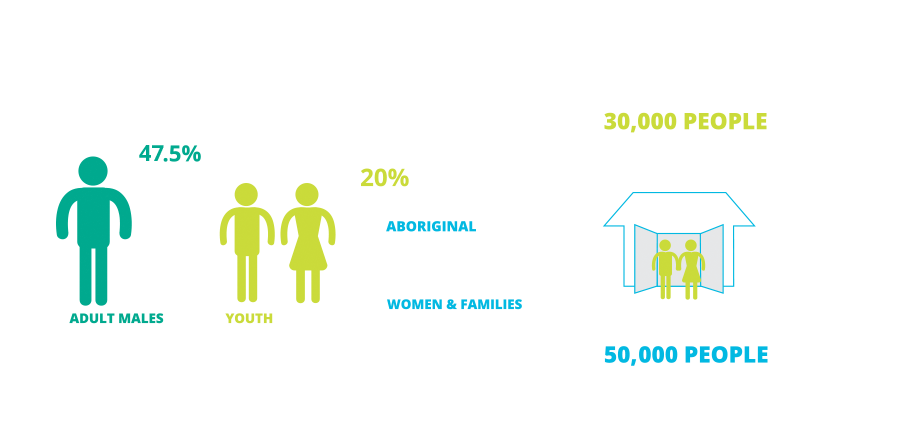

It is estimated that 200,000 Canadians will be homeless over the course of a year.7 The prevalence of mental health issues is significantly higher for Canadians who are homeless, compared with the general population. The Mental Health Commission of Canada estimates that there are approximately half a million people diagnosed with a mental illness in Canada who are inadequately housed, with more than 100,000 of those individuals being homeless.8 Studies suggest that between one-quarter and one-third of Canadians who are homeless experience serious mental illness.9

In Canada, the annual estimated cost of homelessness is $7 billion.10 Individuals who are homeless are often heavy users of criminal, health, and social services, and the costs associated with this use is higher for people who are homeless than for individuals with housing.11 By targeting people who are chronically homeless using the Housing First approach, resources can be better directed to strategies that have been shown to work for this population.

What are the origins of Housing First?

Following the widespread closure of psychiatric hospitals that occurred between the 1960’s and 1980’s (a period termed “deinstitutionalization”), there was a movement towards community-based mental health treatment. The early housing models that followed deinstitutionalization combined psychiatric and addiction treatment, and mandated treatment compliance and sobriety as prerequisites and conditions for obtaining and keeping housing. This model — often termed the “continuum” or “staircase” model — came under critique in the 1980s on the grounds that: (a) there is a lack of consumer choice about housing and neighbourhoods; (b) community integration is hindered by confinement to specific neighbourhoods and buildings; (c) social relationships are disrupted by movements along the continuum of housing that was offered under the previous model of supportive housing: and(d) the most vulnerable individuals tend to become caught cycling between inpatient psychiatric care and involvement with the justice system.12

Housing First emerged in response to these critiques of the continuum model in the late 1980’s. Supported by consumer advocates, Ridgeway and Zipple,13 Dr. Paul Carling espoused an approach that he called “supported housing,” which gave consumers choice in immediate permanent housing located in “normal” rental units. This model was taken up and brought to mainstream attention in the early 1990’s by Dr. Sam Tsemberis and the organization Pathways to Housing in New York City. A particular innovation of the Pathways model was to bring supported housing together with (off-site) support provided by a recovery-oriented ACT team for the benefit of people who had experienced both homelessness and mental illness. By itself, ACT had proven to be ineffective in a homelessness context. Brought together, these two models (supported housing and ACT) became a powerful combination. Over the next decade, the Pathways Housing First model emerged as probably the most well-developed and researched Housing First program.

How does Housing First work?

Housing First seeks to end homelessness by providing immediate access to permanent housing in the community.

Housing First seeks to end homelessness by providing immediate access to permanent housing in the community. When participants enter the program, they are provided immediate access to housing through a team that is responsible for helping participants find and get housing. A care plan is then prepared by the participant in collaboration with an ACT team or case manager, including immediate attention to helping the participant apply for disability benefits, which is important for lease eligibility. The participant forms a working alliance with her or his clinical service team or worker and identifies unique treatment goals. Clinical service teams help participants to access community health services for acute and chronic health issues. Participants are then offered assistance in pursuing their treatment goals. These goals might include vocational training and support in establishing and re-establishing social, familial, and spiritual connections. These interventions are intended to produce housing stability, participation in treatment services, and decreases in emergency service utilizations. Additionally, these interventions are intended to promote community integration14.

Click here to view more Canadian examples of Housing First models.

What are the core principles of Housing First?

Immediate access to permanent housing with no housing readiness requirements

Individuals are given immediate access to housing without proving they are “ready” for housing or participating in substance-abuse or psychiatric treatment. One idea behind this is that people will eventually become motivated to pursue treatment (or may find alternative ways of managing their mental health issues or addictions) in order to keep their housing. Additionally, housing and clinical services are separated to ensure that clinical service use can change without a housing move, and that a person can stay connected to her or his mental health team even if the individual becomes temporarily homeless. Individuals can also choose to change housing without this impacting their clinical services.

Individuals are given immediate access to housing without proving they are “ready” for housing or participating in substance-abuse or psychiatric treatment. One idea behind this is that people will eventually become motivated to pursue treatment (or may find alternative ways of managing their mental health issues or addictions) in order to keep their housing. Additionally, housing and clinical services are separated to ensure that clinical service use can change without a housing move, and that a person can stay connected to her or his mental health team even if the individual becomes temporarily homeless. Individuals can also choose to change housing without this impacting their clinical services.

Consumer choice and self-determination

Participants are able to have some choice in the type of housing they want as well as location — although choice may be constrained by the conditions of the local housing market. Housing choice may include non-scattered site options, including congregate housing, if that is what the participant wants. Housing allowances are important in ensuring choice of housing unit. Additionally, treatment is guided by participant choice.

Participants are able to have some choice in the type of housing they want as well as location — although choice may be constrained by the conditions of the local housing market. Housing choice may include non-scattered site options, including congregate housing, if that is what the participant wants. Housing allowances are important in ensuring choice of housing unit. Additionally, treatment is guided by participant choice.

Individualized, recovery-oriented, and client-driven supports

Participants’ needs will vary considerably with some individuals requiring minimum supports while others might require intensive supports for the rest of their lives. Supports range from ICM, where support is coordinated by a case manager, to ACT, where support is coordinated by a multidisciplinary team. Treatment and supports should be both voluntary and congruent with the unique social and individual circumstances of each participant, and consistent with a recovery orientation.

Participants’ needs will vary considerably with some individuals requiring minimum supports while others might require intensive supports for the rest of their lives. Supports range from ICM, where support is coordinated by a case manager, to ACT, where support is coordinated by a multidisciplinary team. Treatment and supports should be both voluntary and congruent with the unique social and individual circumstances of each participant, and consistent with a recovery orientation.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction refers to a public health strategy to substance use that emphasizes minimizing the negative consequences of use. The aim of harm reduction is to reduce both the risks and effects associated with substance use disorders and addiction at the level of the individual, community, and society without requiring abstinence. Subsequently, Housing First does not have sobriety requirements and participants’ substance use will not result in a loss of housing unless their behaviour violates the terms of their lease. Housing First teams will use these occasions for enhanced intervention and treatment.

Harm reduction refers to a public health strategy to substance use that emphasizes minimizing the negative consequences of use. The aim of harm reduction is to reduce both the risks and effects associated with substance use disorders and addiction at the level of the individual, community, and society without requiring abstinence. Subsequently, Housing First does not have sobriety requirements and participants’ substance use will not result in a loss of housing unless their behaviour violates the terms of their lease. Housing First teams will use these occasions for enhanced intervention and treatment.

Social and community integration

Community integration — the meaningful psychological, social, and physical integration of individuals who were formerly homeless and living with mental health issues — is an important part of the Housing First model and is facilitated by the separation of housing and clinical services. Participants should be given opportunities for meaningful participation in their communities. Community integration is important in terms of preventing social isolation, which can undermine housing stability.

Community integration — the meaningful psychological, social, and physical integration of individuals who were formerly homeless and living with mental health issues — is an important part of the Housing First model and is facilitated by the separation of housing and clinical services. Participants should be given opportunities for meaningful participation in their communities. Community integration is important in terms of preventing social isolation, which can undermine housing stability.

What are the key components of Housing First?

Housing

Housing should be guided by the principle of consumer choice and self-determination. Participants should be able to have some choice about unit type (scattered site, congregate) and neighbourhood preference, although choices will, in many cases, be contingent on the conditions of the local housing market. Additionally, participants should not make up more than 20 per cent of renters in a specific unit and should not pay more than 30 per cent of their income towards rent.

Housing Supports

A Housing Team assists participants in selecting housing of their choice. Responsibilities of the Housing Team include:

- Helping participant search for and identify appropriate housing

- Building and maintaining relationships with landlords, including mediating during times of conflict

- Applying for and managing housing allowances

- Assistance in setting up apartment

- Independent living skills development

Clinical Supports

A Clinical Team provides a range of recovery-oriented, client-driven supports. Supports range from ICM, where support is coordinated by a case manager, to ACT, where support is coordinated by a multidisciplinary team. These supports address health, mental health, social care, and other needs. Effective assessments at enrolment are important for matching the right participants with the right supports. These supports are aimed at promoting community integration and improving quality of life and independent living. These supports may include:

- Life skills for maintaining housing, establishing and maintaining relationships and engaging in meaningful activities.

- Income support

- Vocational assistance, such as enrolling in school, finding employment, or volunteering

- Managing addictions

- Community engagement

Upon learning about Housing First, many service providers will say that they have already been doing Housing First. While many housing and support programs for people who are homeless operate from a basis of recovery, individualized and consumer-directed services, and a focus on community integration, supportive housing programs are less likely to adhere to two important components of Housing First: housing choice and structure and the separation of housing and support services. In this table, we clearly delineate the key elements of these two components to show where potential differences may lie across programs and initiatives. The second column provides items from a Housing First fidelity scale based on the Pathways to Housing program;15 the third column is based on a literature review on supported Housing First;16 the fourth column is from a recent, widely distributed book on Housing First in Canada;17 and the last column contains key elements from the federal Homelessness Partnering Strategy’s (HPS) position on Housing First.18

Click here for more information on HPS and Housing First.

From this table, we can see that the recent book on Housing First in Canada and the HPS position on Housing First overlap to a large extent with the Pathways to Housing program and the literature. However, there are some divergences as well. Scattered site housing with housing subsidies and standard landlord-tenant leases are emphasized, but they are seen as not necessary for Housing First. As well, the two Canadian sources are silent on whether support services must be provided outside of the housing site and whether separate agencies must operate housing and support. To be clear, in this toolkit, we are emphasizing adherence to the original Pathways to Housing model, on which numerous applications in the U.S.19 and in Canada and Europe20 are based.

What is Housing First – A Philosophy, a system approach, or a program model?

Housing First is an overarching philosophy with a core set of principles that have implications for systems approaches to ending homelessness and for program models. The core principles described earlier (e.g., immediate access to permanent housing with no housing readiness requirements, consumer choice and self-determination) underlie and guide both systems approaches to ending homelessness and program models.

A Housing First systems approach focuses on cohesive community planning to develop coordinated, complementary programs and policies to end homelessness that are consistent with Housing First principles and practice. These feature a common intake system to Housing First programs, whether from the street, from emergency shelters, or people coming out of institutions who are at risk of becoming homeless.

Housing First as a program focuses on specific program models targeted at particular homeless populations (e.g., adults with mental illness and co-occurring addictions, families with children, youth) to reduce or eliminate homelessness and promote the well-being of these populations. The distinctions between systems and program interventions, and their alignment with the principles of Housing First, are depicted in this table.

How is Housing First different from supportive housing approaches?

Most supportive housing approaches or “continuum of care” models provide housing only in places with built-in clinical support services. This means that the landlord and service-provider functions are integrated in the same agency. Additionally, supportive housing approaches often mandate clients to achieve and maintain sobriety, in addition to receiving ongoing psychiatric services.

Housing First houses participants immediately, without any preconditions. Housing and clinical services are separated. Participants are offered an array of health, mental health, and other support services after they are housed.

In contrast, Housing First houses participants immediately, without any preconditions. Housing and clinical services are separated. Participants are offered an array of health, mental health, and other support services after they are housed. Participants choose housing, as well as which support services will best meet their needs and meet with a case manager or support staff person on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. In contrast to some other approaches, Housing First uses a harm reduction approach. The aim of harm reduction is to reduce both the risks and effects associated with substance use disorders and addiction, without requiring

The continuum, or supportive housing approach, is an important part of mental health and housing services for adults who are homeless. Housing First is an evidence-based approach that targets individuals who have not been well served by traditional approaches.

Why does Housing First emphasize consumer choice?

Housing First addresses the critique of advocates and researchers that traditional approaches to housing and service provision for adults with mental health and addictions issues tend to ignore the importance of choice. Additionally, consumers themselves have long advocated a desire to live in apartments in the community. If individuals with mental health issues who are homeless are to be positioned as full citizens, it is important to recognize that they are experts of their own lives who have been repeatedly failed by systems that have not worked and have often been characterized by a lack of choice. With Housing First, participant choice allows for these individuals to pursue choices that they see as meaningful and valuable. Promoting choice is an effective way to engage consumers in the recovery process.21, 22 Consumer choice over housing and services also promotes feelings of self-efficacy and self-determination in other aspects of life.

Housing First addresses the critique of advocates and researchers that traditional approaches to housing and service provision for adults with mental health and addictions issues tend to ignore the importance of choice. Additionally, consumers themselves have long advocated a desire to live in apartments in the community. If individuals with mental health issues who are homeless are to be positioned as full citizens, it is important to recognize that they are experts of their own lives who have been repeatedly failed by systems that have not worked and have often been characterized by a lack of choice. With Housing First, participant choice allows for these individuals to pursue choices that they see as meaningful and valuable. Promoting choice is an effective way to engage consumers in the recovery process.21, 22 Consumer choice over housing and services also promotes feelings of self-efficacy and self-determination in other aspects of life.

How does Housing First promote recovery?

Housing First promotes recovery largely in terms of its person-centred approach to care and wellbeing. This person-centred approach reflects the idea that housing is a basic human right and that social justice is a guiding philosophy of Housing First. Consumer choice and self-direction are key components of both housing and clinical services. Clinical services are provided by either an ACT team or an ICM team. There is a strong emphasis on staffing in Housing First, where it is integral to get “the right people” who promote empowerment and view program participants through a strengths-based lens. Empowerment is an important principle of support because Housing First seeks to bolster the ability of participants to respond to life challenges. Consistent with an empowerment approach, support services are centered on a strengths-based orientation as opposed to a deficit model.23

These NFB films show empowerment is an important principle of support.

Where has Housing First been implemented?

Myth

Housing First is from the United States and only relevant within the United States.

Myth Busted

Housing First has been widely implemented in Canada and throughout the world.

Housing First has been widely implemented in North America and is starting to be implemented in Europe. In North America, it has been implemented in both Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick) and the United States (New York, South Carolina, Oregon, Massachusetts, Minnesota, California). In Alberta, where there is a 10-year plan to end homelessness, Housing First has been implemented province-wide. In Europe, Housing First has been implemented in Ireland, Portugal, Finland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Denmark, Scotland, and France.24, 25 While Housing First started as a strategy to address homelessness for people with mental health issues, in a number of places it is being used with the broad homeless population.

Provinces, states and countries with documentation of Housing First implementation

What is the evidence base for Housing First in Canada?

At Home/Chez Soi, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Housing First in Canada, upon which this toolkit is based, provides evidence of the effectiveness of the Housing First model. Additionally, a total of nine RCTs of Housing First have been conducted in the United States. Results of these RCTs have consistently shown that Housing First reduces homelessness and hospitalization and increases housing stability and housing choice significantly more than treatment as usual (TAU) and supportive housing or case management services alone. Some of these studies have found that Housing First has facilitated improvements in health, substance use, and community integration as well.26 Housing First has been endorsed by the Employment and Social Development Canada’s (HRSDC) Homelessness Partnering Strategy. It has also been included in the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP, 2007).27

In Canada specifically, there have been some positive findings about the implementation of Housing First:28

- In Vancouver, At Home/Chez Soi was cited as one of the reasons for a reduction in homelessness, as calculated by a count.

- Recent research in Vancouver estimates a cost savings of 30 per cent by giving people who are homeless stable housing.

- Housing First in Calgary has been so successful there have been shelter bed closures.

- A Canadian study found traditional institutional responses to homelessness (the prison system and psychiatric hospitals) substantively more expensive (estimated annual costs: $66 000 – $120 000) than investments in supportive housing (estimated annual costs: $13 000 – $18 000)

At Home/Chez Soi has substantively added to the evidence base for Housing First in Canada. This study found the following:29

Program Implementation

The study demonstrated that Housing First can be implemented in different Canadian contexts using both ACT and ICM. The model can serve individuals with different levels of care needs and be adapted to local contexts including rural and small city contexts and diverse populations (Aboriginal and recent immigrant populations).

Housing First rapidly ends homelessness

Across all cities, participants receiving Housing First retained housing at a much higher rate than treatment as usual participants. In the last six months of the study, 62 per cent of Housing First participants were housed all of the time (versus 31 per cent for treatment as usual), while 22 per cent were housed some of the time (versus 23 per cent for treatment as usual), and 16 per cent none of the time (versus 46 per cent for treatment as usual). Findings were similar for ACT and ICM participants. Housing First residences tended to be of better quality and more consistent than treatment as usual residences.

Housing First is a sound investment

The cost of Housing First is, on average, $22,257 per year per high needs participant and $14,177 per year per moderate needs participant. In the two-year period after participants entered the study, every $10 invested Housing First services resulted in an average savings of $9.60 for high needs participants receiving ACT and $3.42 for moderate needs participants receiving ICM. There were significant savings for the 10 per cent of participants who had the highest costs at study entry. Over the two-year study, a $10 investment in Housing First services resulted in an average savings of $21.72 for these participants.

Having a place to live with supports can lead to other positive outcomes…

…above and beyond those provided by existing services.</strong> Quality of life and community functioning improved for Housing First and TAU participants, and improvements in these broader outcomes were significantly greater in Housing First, in both service types (ACT and ICM). Symptom-related outcomes, including substance use problems and mental health symptoms improved similarly for both Housing First and TAU participants, but since most existing services were not linked to housing there was much lower effectiveness in ending homelessness for TAU participants.

There are many ways in which Housing First can change lives.

While the Housing First groups, on average, improved more and described fewer negative experiences than TAU, there was great variety in the changes that occurred. People with serious substance use problems, for example, tended to do more poorly than others irrespective of study group, although a majority of those in the Housing First group still achieved stable housing.

Getting Housing First right is essential to optimizing outcomes.

Housing stability, quality of life, and community functioning outcomes were all more positive for programs that operated most closely to Housing First standards. This finding indicates that investing in training and technical support can pay off in improved outcomes.

How can the Housing First model be adapted?

Housing First can be adapted for a number of groups experiencing homelessness. This toolkit provides information on Housing First for individuals who are chronically homeless with mental health and addiction needs, specifically. While Housing First is implemented in urban areas most frequently, it can be adapted and implemented almost anywhere. At Home/Chez Soi has been implemented in five different Canadian cities. Each city has adapted the Housing First intervention to meet the specific needs of its participants.

While Housing First is implemented in urban areas most frequently, it can be adapted and implemented almost anywhere.

See the map below to find out more about how the At Home/Chez Soi adapted the HF intervention to meet the needs of its participants.

How does Housing First improve the quality of life of participants?

Housing First has been shown to promote a sense of autonomy, improve health and mental health, and to allow participants to begin orienting toward future goals and social relationships.30 Housing First may also enable participants to reclaim a valued identity.31

View these clips from the National Film Board and Pathways to Housing to see how participants experience the Housing First intervention.

1. Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Journal Information, 94(4).

2. Tsemberis, S. (2010). Housing First: The Pathways model to end homelessness for people with mental illness and addictions. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Permanent supportive housing evidence-based practices kit. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

4. Tsemberis, S., & Asmussen, S. (1999). From streets to homes: The pathways to housing consumer preference supported housing model. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 17(1-2), 113-131.

5. Kuhn, R., & Culhane, D. P. (1998). Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: Results from the analysis of administrative data. American journal of community psychology, 26(2), 207-232.

6. Aubry, T., Farrell, S., Hwang, S. W., & Calhoun, M. (2013). Identifying the Patterns of Emergency Shelter Stays of Single Individuals in Canadian Cities of Different Sizes. Housing Studies, (ahead-of-print), 1-18.

7. Gaetz, S., Donaldson, J., Richter, T., & Gulliver, T. (2013). The state of homelessness in Canada 2013. Retrieved on June, 23, 2013.

8. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Turning the key: assessing housing and related supports for persons with mental health problems and illness. Ottawa, Ontario: MHCC, 2012.

9. Hwang, S. W., Stergiopoulos, V., O’Campo, P., & Gozdzik, A. (2012). Ending homelessness among people with mental illness: the At Home/Chez Soi randomized trial of a Housing First intervention in Toronto. BMC public health,12(1), 787.

10. Gaetz, S., Donaldson, J., Richter, T., & Gulliver, T. (2013). The state of homelessness in Canada 2013. Retrieved on June, 23, 2013.

11. Eberle, M. P. (2001). Homelessness, Causes & Effects. Volume 3: the Costs of Homelessness in British Columbia. Ministry of Social Development and Economic Security.

12. Nelson, G., & Laurier, W. (2010). Housing for people with serious mental illness: Approaches, evidence, and transformative change. J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare, 37, 123.

13. Ridgway, P., & Zipple, A. M. (1990). The paradigm shift in residential services: From the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 13(4), 11.

14. Carling, P. J. (1995). Return to community: Building support systems for people with psychiatric disabilities. Guilford Press.

15. This is the Pathways Housing First model as taken up by At Home/Chez Soi.

16. Stefancic, A., Tsemberis, S., Messeri, P., & Drake, R.E. (in press). The Pathways Housing First Fidelity Scale for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation.

17. Tabol, C., Drebing, C., & Rosenheck, R. (2010). Studies of “supported” and “supportive” housing: A comprehensive review of model descriptions and measurement. Evaluation and program planning, 33(4), 446-456.

18. Gaetz, S., Scott, F., & Gulliver, T. (2013). Housing First in Canada: Supporting communities to end homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press.

19. Homelessness Partnering Strategy. HPS Housing First Approach (2013). Employment and Social Development Canada.

20. Tsemberis, S. (2012). Housing First: Basic Tenets of the Definition Across Cultures. European Journal of Homelessness, 6(2), 169.

21 Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Journal Information, 94(4).

22 Padgett, D. K. (2007). There’s no place like (a) home: Ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 64(9), 1925-1936.

23 Adapted from: Nelson, G., Goering, P., & Tsemberis, S. (2012). Housing for people with lived experience of mental health issues: Housing First as a strategy to improve quality of life. In C. J. Walker, K. Johnson, & E. Cunningham (Eds.), Community psychology and the economics of mental health: Global perspectives (pp. 191-205). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan

24 Greenwood, R.M., Stefancic, A., Tsemberis, S., & Busch-Geertsema, V. (2013). Implementations of Housing First in Europe: Successes and challenges in maintaining model fidelity. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 16, 290-312.

25 Busch_Geertsema, V. (2013). Housing First Europe: Final report. Bremen/Brussels: European Union Programme for Employment and Social Solidarity.

26 Aubry, T., Ecker, J., Jette, J. Supported housing as a promising housing first approach for people with sever and persisting mental illness in Guirguis, M., McNeil, R., & Hwang, S. eds. Homelessness and Health. In press.

27 http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/

28 Mental Health Commission of Canada. At Home/Chez Soi Early Findings. 2012.

29 Mental Health Commission of Canada. Main Messages from the Cross-Site At Home/Chez Soi project. 2013.

31 Gillis, L., Dickerson, G., & Hanson, J. (2010). Recovery and homeless services: New directions for the field. Open Health Services and Policy Journal,3, 71-79.